These two concepts are nowhere near as far apart as they might seem at first glance. In fact, they share a great deal. Punk rejects authority, social norms, and hypocrisy. Buddhism, on the other hand, does not worship the Buddha as some kind of supernatural being; it emphasizes personal experience, practice, and understanding one’s own mind. It also rejects blind obedience to the ego and its illusions. Punk likewise rejects idols and all those pop stars treated as modern-day gods.

Punk screams out its pain and frustration, while Buddhism tries to understand it. Punk says “do it yourself,” Buddhism says “no one will save you — you have to do it yourself.” Punk sends its message outward, Buddhism directs its message inward. Punk’s solidarity with outsiders mirrors the Buddhist understanding of compassion — not in the sentimental sense of “I feel sorry for you,” but as the courage to remain open in a harsh and unforgiving world. All of this explains why so many people from the punk scene find something in Buddhism that gives them direction without forcing them to abandon their authenticity. The shared goal of both Buddhism and punk is, ultimately, freedom.

Dharma Punx

Noah Levine is a punk from Santa Cruz, California, who grew up in an environment full of anger and disillusionment. The punk scene gave him an identity, but it also pulled him into a spiral of self‑destruction. Noah has been practicing Buddhism since 1988. He turned to Buddhist meditation to recover from addiction, and he has remained successfully sober ever since. His first book, Dharma Punx, was published in 2003 and helped spread the Buddha’s teachings within his generation.

The book connects two seemingly incompatible worlds: the aggressive punk subculture and the calm discipline of Buddhist practice. It also captures the frustration of young people who felt betrayed by their parents’ ideals, and it inspires inner transformation. Noah’s punk spirit never disappeared — it simply changed form. His rejection of authority and dogma gradually shifted from fighting police and the system to a much deeper rebellion: questioning his own ego, suffering, and the destructive patterns that keep people trapped.

The DIY ethic is reflected in his founding of meditation centers, communities, and a recovery program that operates outside traditional institutions and relies on personal experience and practice. His teaching style remains raw and unpolished. Levine has no need to wrap Buddhism in new‑age glitter. He speaks directly, sometimes harshly, but always authentically. That honesty attracts people who feel out of place in mainstream spiritual circles.

A strong part of his work is solidarity with those on the margins. Noah has long worked with people in treatment, in prisons, and in communities society tends to overlook. Where others see a problem, he sees a human story and the possibility of change. This is where his punk roots and Buddhist practice intersect most clearly. In 2007 he founded the Buddhist meditation society Against the Stream. In 2008 he created and implemented the Buddhist addiction‑recovery program Refuge Recovery.

When I’m traveling through London in the summer on public transport — which, for reasons unknown to me, still has no air‑conditioning — and I’m sweating like a barn door, I’d much rather listen to Noah’s calm voice on his podcast than to Exploited. Maybe that’s why I haven’t killed anyone yet.

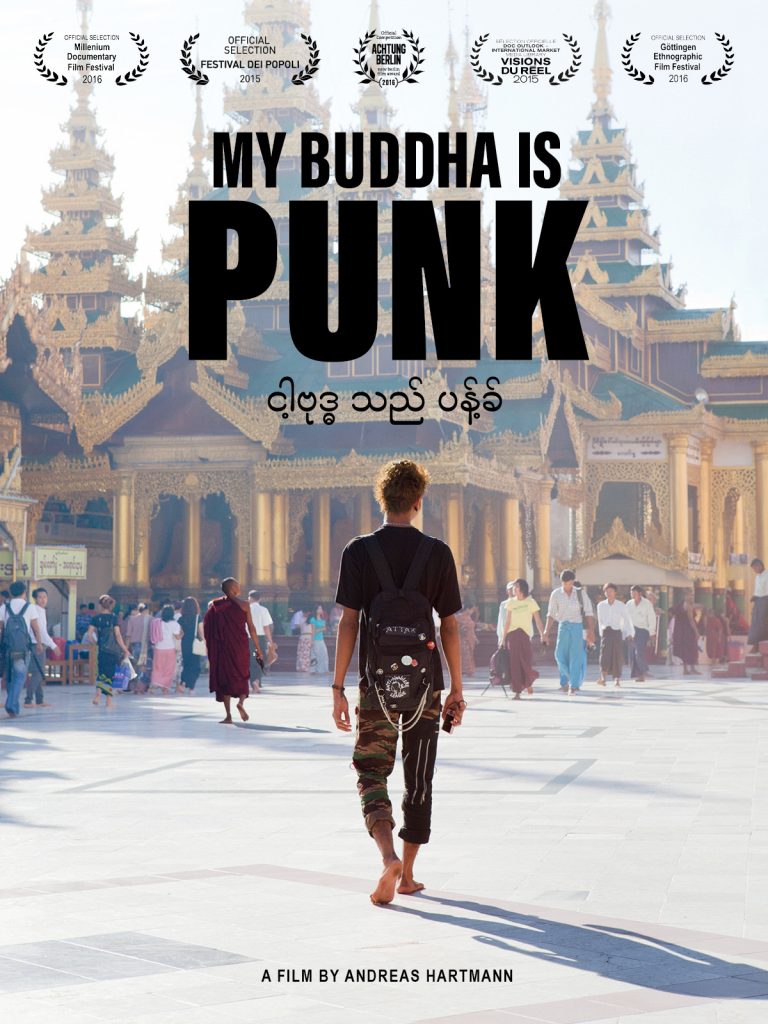

My Buddha Is Punk

My Buddha Is Punk is a fascinating documentary by German director Andreas Hartmann from 2015, following the life of Kyaw Kyaw, a twenty‑five‑year‑old punk from Myanmar. Kyaw tries to develop the local punk scene while also drawing attention to human‑rights violations, the ongoing civil war, and the persecution of ethnic minorities, especially Muslim Rohingya.

Through music, traveling across the country, and public demonstrations, he spreads his own philosophy of combining Buddhism and punk — a philosophy that rejects both religious and political dogma. The film shows that Myanmar has a current of “Buddhist fundamentalism” that supports discrimination and violence against minorities. Kyaw, himself a practicing Buddhist, asks how a religion founded on non‑violence can be used to justify oppression. Where does spiritual tradition end and political ideology begin?

Kyaw is also the frontman of the punk band The Rebel Riot, with whom he will perform in the United Kingdom in mid‑April for the first time in nine years. This time together with The Restarts and others at London’s 100 Club. And I definitely won’t miss it.