How political disillusionment can become a catalyst for life-changing decisions. About leaving the Czech Republic, searching for freedom, and witnessing the slow demise of a once-powerful party.

It will soon be fifteen years since I left the Czech Republic for good. But the decision had been slowly ripening inside me for five years before that.

I remember it like it was yesterday. At the end of July 2005, I watched on TV the brutal police crackdown on participants of CzechTek in Mlýnec—personally ordered by then-social democratic Prime Minister Paroubek. Watching riot police beat young people marked the end of the euphoria and carefree spirit of the 1990s for me. It brought back memories of crackdowns during the communist regime. Stories told by eyewitnesses came flooding back—like in 1974, when communist police in Rudolfov brutally beat attendees of a concert by The Plastic People of the Universe. Then came my own experiences from the late 1980s, when police, in the best-case scenario, would shut down punk and underground concerts—like Visací zámek’s gig in Hronovická Street in Pardubice—or, more often, beat and arrest people, like at the event near Kunětická hora.

It was a shock. A rude awakening. I watched as cronyism, authoritarian practices, and everything I despised about the old regime began to creep back in.

That was when I stopped voting for the ČSSD for good. I went to protests, signed petitions, wrote emails to MPs—and a few years later, I even took part in the legendary egg-throwing at ČSSD leaders. As the moral decay deepened and spread from politics into society, I came to the decision to leave the Czech Republic permanently. The preparations took me about a year.

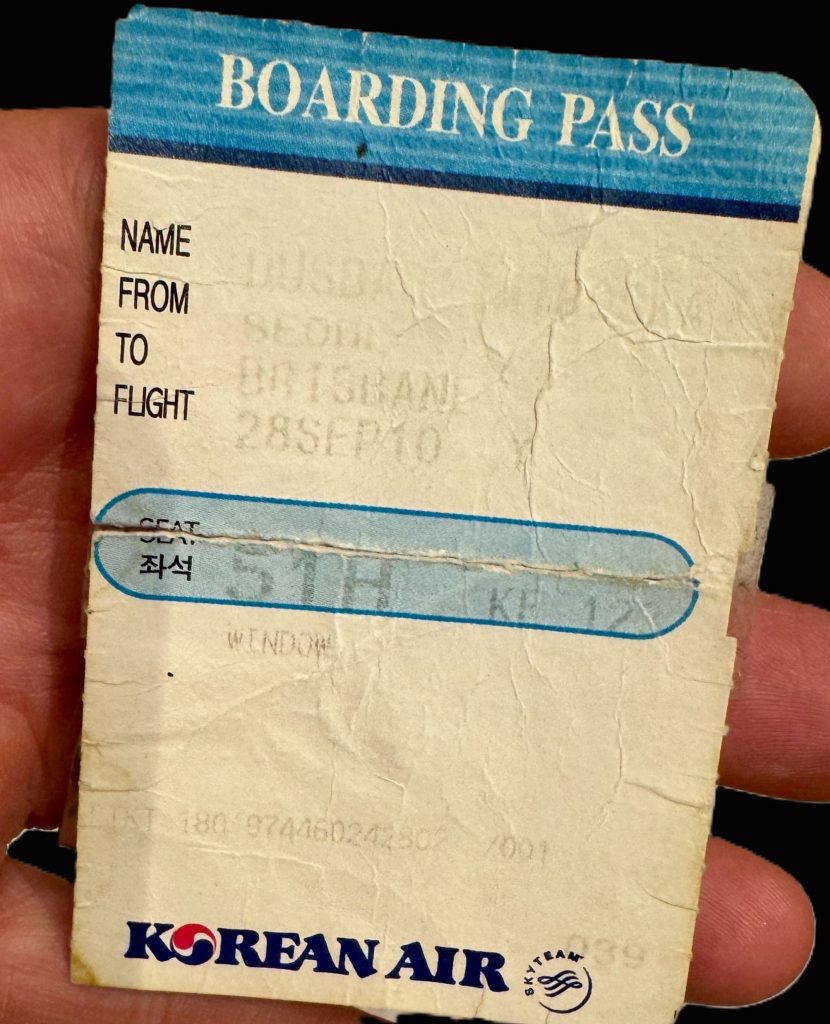

On 28 September 2010, I boarded a plane in Prague—first to Seoul, then on to Brisbane. A new chapter of my life began, one that would take me first to Australia for a few years, and later here to London. Over the years, I’ve traveled a vast part of the world. I’ve seen extreme poverty and breathtaking wealth. I’ve crossed deserts and rainforests—and most importantly, I’ve met many amazing and fascinating people. The best decision of my life—one I would paradoxically never have made if it weren’t for Prime Minister Paroubek.

Epitaph

I sit in my London flat, a British passport in my drawer, and watch in real time as the oldest Czech political party—now just an empty shell—writhes in its death throes. For me, it’s been fifteen years of an incredible life. For it, fifteen years of painful dying.